The company’s long history means that it has continued trading throughout much social and technological change; through economic difficulties; as well as through many periods of war. It is inevitable that this history will include direct and indirect links to the making of weapons and military equipment.

The company and family papers can offer some insight into how the company, employees and the community at Hay Mills were affected during the two major conflicts of the twentieth century.

World War I

In the three years preceding the outbreak of World War I, Webster and Horsfall’s production was at just over 5,000 tons of wire per annum. Their ‘fine spring wire’ was used by piano makers but also in the making of many things, including ordnance. The development of the bicycle and motor car industries meant that their wire and spring wire was used for bicycle spokes and saddles; as beading for car tyres; and their flat section wire was used for the winding of naval gun barrels.

In 1913, Latch and Batchelor was producing 4,000 tons of wire rope. The company sold their products world wide and a global conflict inevitably brought consequences. Latch and Batchelor’s main customer for its locked coil aerial ropes was a German company. This extensive trade collapsed overnight in August 1914.

However, there was soon a military demand for wire.

Fuse Wire

The armament industry was placed under government control in 1914 and the factory at Hay Mills was one of the earliest factories to be taken over by the Admiralty. Despite the formation of The Ministry of Munitions in 1915, the company remained under the control of the Admiralty throughout the war.

Ammunition was made in Britain but also bought in from other countries. In 1915 the company was consulted over problems with premature shell bursts, the failures involved defective fuse equipment. A secret meeting of a representative of the Ministry of Munitions and the company’s general manager, Frank Luckman, was held at the Midland Hotel in the city. Luckman gave his expert opinion on the fuse spring presented to him. He confirmed it was of inferior quality, easily broken and the wire used, certainly not of Webster and Horsfall’s making.

An army enquiry had already confirmed the suspicion that the current supply of shell fuses was unreliable and prone to premature shell bursts, killing and wounding soldiers before it could even be fired at enemy lines.

The stockpile of foreign supplied fuses had to be condemned which meant the shells were in short supply. From then on, due to the reputation of the company’s wire, the Ministry of Munitions issued instructions that all the replaced springs must only be made from wire manufactured by Webster and Horsfall. This was an enormous responsibility ensuring an output to fulfil the requirements of the army for the duration of the war.

The company became the sole manufacturer of shell fuse spring wire, according to records, producing 80,260 miles of fuse wire. This was along with anti-submarine netting and mine, aircraft and balloon cables. The company also went on to be involved in the development of a wire for use in the engine valve springs for aircraft.

Reserved Occupation and War Work

Wire drawing was a skilled occupation and the company had lost some of its most experienced workers to the war. In fact, the situation was considered so serious with the task before them as sole suppliers of fuse wire, that company employees who were in service were ‘loaned’ back to the factory, working in their uniforms at military rates of pay. One man was reputed to have been in the trenches in France as a machine gunner and he was fetched out of the line by a runner and appeared at the factory 48 hours later in full military kit.

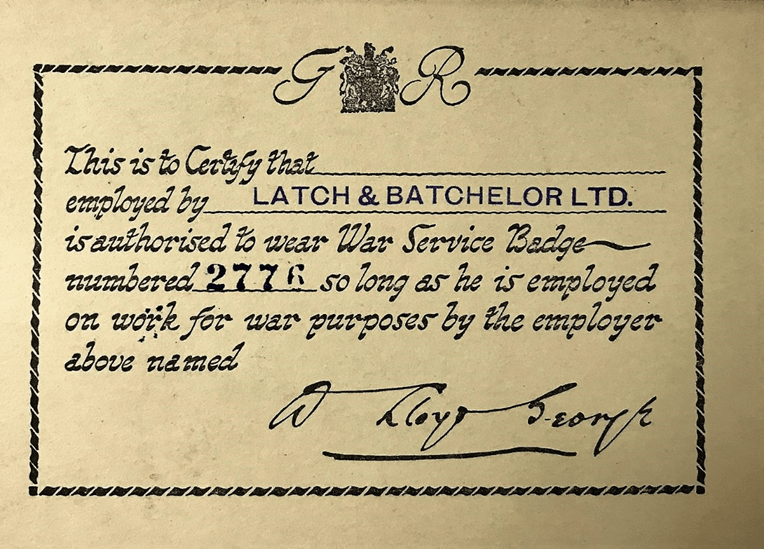

For the men not in uniform, who had not voluntarily enlisted or been conscripted, they were considered as working in a reserved occupation or performing a war service. Public attitudes (before conscription) were often hostile towards men not in uniform, the famous white feather campaign saw men presented with feathers suggesting they were cowards for shirking their duty to their country. War Service Badges became a way of distinguishing men in such roles and a certificate was issued matching a numbered badge with an employee.

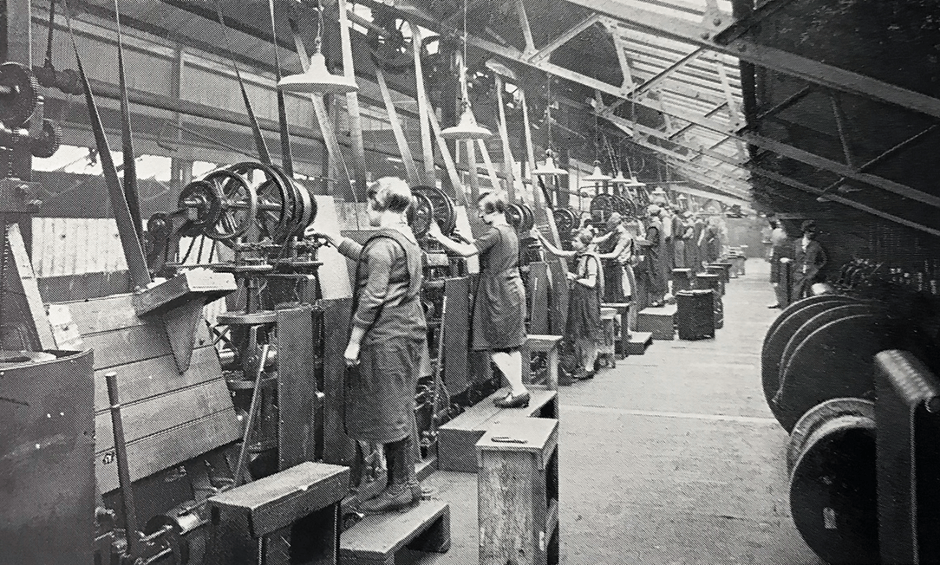

As the war progressed, huge loss of life and then conscription created a severe shortage of labour across all sectors. This saw the introduction of women workers in trades and industries traditionally seen as male only occupations. The company faced the same situation, with a pre-war workforce of about 700, reduced to 542. In 1916 Latch and Batchelor included 50 women in their workforce, seen here operating the machines.

That war-time workforce included not only wire drawers and rope makers but furnace hands, cleaners, galvanisers, tinners, tool makers, packers, clerks, fitters, bricklayers, stokers, plumbers, blacksmiths, electricians and gasmen; all with essential roles to keep the factory operating and meet production targets.

Those who went away to fight

Many of the young men working at the factory at the start of the war, may have already been members of the Territorial Army or like so many of their generation, eagerly rushed to enlist to fight for their country, in what everyone assumed would be a short war. At the very start, there was no government policy to discourage or prevent skilled workers in essential industries enlisting. This would be a lesson learnt and would not be repeated in the next conflict.

The records do not offer a lot of information about those who left to serve their country. However, there is a wooden memorial plaque inside St. Cyprian’s church which lists over 100 names of those from the parish who fell during 1914-18. As the church is so inextricably linked to the company, it is likely that workers from the factory or the relations of workers are included in this roll. One employee named in The Iron Masters of Penn, was George Goode, he died with his shipmates on the HMS Good Hope when it was lost in November 1914.

Some employees thankfully returned, and were recognised for their service; George Carter, Tom Lowe and John Salisbury were all awarded the Military Medal.

Private Arthur Laishley (later promoted to L/Corporal), was awarded the Military Medal and the Distinguished Conduct Medal. His citation reveals that he was honoured for conspicuous gallantry at Sommaing on 24 October 1918. With his section in an advanced post, they maintained position for over ten hours against enemy counter-attacks, until relieved. The section suffered a fifty per cent casualty rate. Arthur was employed as a fitter and remained with the company until his retirement in 1960.

Members of the managing families also served. Henry Coldwell-Horsfall’s son James, was already a military man and following the outbreak of war was posted to the Expeditionary Force in Belgium. Thankfully, he was returned home to his wife and young children in 1919.

Three sons of Arthur Latch also served during the conflict. Cyril Latch, who had joined his father at the company in 1906, enlisted in August 1914; first with the Royal Field Artillery and then the Royal Flying Corps. His brother, Arthur Roy Latch was commissioned in January 1917 as a second lieutenant with Royal Tank Corps. Sadly their younger brother, Clive Chartress Latch, who had briefly worked at Latch and Batchelor, was with the Inniskilling Fusiliers when he was killed in action in France on 28 June 1916; he was 25 years old.

World War II

Once again, the company was placed under government control and there was huge demand for fuse wire, but technology and warfare had advanced and changed. There was a greater demand for spring materials for use in the making of light weapons, vehicles and of course, aircraft.

Women, once more, formed an essential part of the wartime workforce and Latch and Batchelor were advertising in the Birmingham Mail in January 1943 for women over the age of 31, for essential war work. They offered full or part-time roles with good wages and a canteen.

Despite workers not being removed from the factory to fight, there was still personal heartache to the owning families. The Latch family suffered yet another loss; Clive Latch (son of Cyril), was a midshipman on H.M.S. Jervis Bay and died on 3 November 1940, aged 17 years.

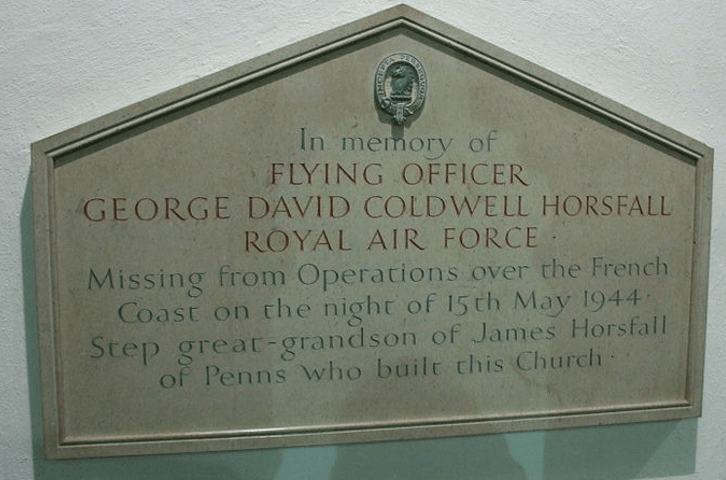

George David Coldwell-Horsfall (great-grandson of James Horsfall), was 22 years old and a Flying Officer with the Royal Air Force when he died in May 1944. He had spent a year at Hay Mills learning to draw wire. His memorial can be found in St. Cyprian’s church.

Other Coldwell Horsfall brothers also saw service with Spitfire pilot, James Michael, briefly a prisoner of war during the war. John Henry returned with the Irish Brigade from Austria at the end of February 1946. Both joined the company directly after the war to steer the company through difficult times.

Birmingham Blitz

The city was an important industrial and manufacturing location and was therefore subject to enemy bombing campaign between August 1940 – April 1943. Many of the city’s factories had been turned over to producing for the war effort and the Hay Mills factory was not that far away from the British Small Arms (BSA) factory, which suffered a devasting air raid on 19 November 1940, killing 53 employees.

The Hay Mills factory thankfully did not suffer such loss of life but did not escape unscathed during the Blitz, being hit by incendiaries and high explosive bombs, suffering 14 direct hits. This affected production and the plant was stopped for over 100 hours in November 1940. The roof was particularly damaged as it lifted with the explosions, causing all the nail holes to become thousand of tiny water jets every time it rained.

The worst attacks of widespread bombing across the city took place on the nights of 9 and 10 April 1941. The factory was not hit directly, but the bank of the neighbouring canal was breached, and the waters flooded the factory and surrounding area to a depth of four feet. Every electric motor was out of service and the company’s coal stocks were seen floating around the streets. Employees had to work day and night to try and restore some form of production 5 days later. The main crane in the rope mill still shudders half-way down the shop and is believed to be caused by slight track misalignment from this time.

St. Cyprian church was such an important part of community life and during the Blitz a bomb severely damaged the church and destroyed the cottage nearest to it. The Rev. Tait reported in the parish magazine of July 1941, just how badly their congregation had been affected with the removal of members to other areas and the difficulties of no heating.

External damage to St. Cyprian church and the marble reredos depicting the Last Supper behind the altar, c. 1930.

Local residents remember a wedding ceremony taking place at the bombed altar after volunteers cleared away the debris, so the wedding could take place. The marble reredos depicting the Last Supper that was damaged by the bomb was finally removed during the restoration of the church after the war.