Manganese Crucible Steel

John Webster, the founder of the business, began as a stockholder of bar iron and a retailer of iron and brass manufactured goods. Much of his stock of nails, fish hooks and pins were made from wire and Webster began drawing his own wire at the mills in Perry Barr. By the time he passed the business to his son, Joseph, the business spanned every stage of the manufacturing process from forging iron to the finished goods.

Joseph expanded the production of wire to Penns Mill and then diverted his attention to the inventions of the Doncaster watch maker, Benjamin Huntsman. He had been experimenting in the production of steel and eventually produced a high-grade cast steel in clay crucible pots; he called it homogenous metal and it had less impurities.

Huntsman did not patent his process, and many adopted his technique, adapting and improving to produce a better-quality metal. By 1766 Joseph Webster was producing steel, most likely the only source of cast steel in Birmingham at the time, and was manufacturing steel swords, pins, fish hooks and needles.

The next generations of the family continued to produce high quality metals, establishing a national reputation for their products. The steel was used by the Birmingham gun and pistol makers and swordsmiths, the demand directed by the many conflicts of the age.

Joseph III continued to experiment to find better ways to produce high quality steel until, a twist of fate, in the early 1820s. Webster’s forge manager at Killamarsh, John Bird, was travelling on stagecoach and overheard two Sheffield steel men talk about the possibility of adding manganese to the charcoal, iron mix of crucible steel. Bird was so excited by the prospect, he got off the coach and immediately returned to the forge and began experimenting. The resulting manganese crucible steel gave Webster’s a virtual world-wide monopoly on a particular wire product.

The Making of Pure Sound – Music Wire

Music wire (or piano wire) is a specialised steel wire to be made into piano strings. The strings are placed under enormous strain and subject to repeated blows as the instrument is played and constantly re-tuned. Development of the instrument in the early nineteenth-century saw the need for wire of a much higher tensile strength.

The company’s important innovation of manganese crucible steel produced music wire of superior strength. By 1836 it was reported in The Mechanics Magazine that Mr. Webster, of Penns, near Birmingham, had overcome the difficulties with the brittleness of music wire and is ‘furnishing steel wire as near to perfection as anything in the world’.

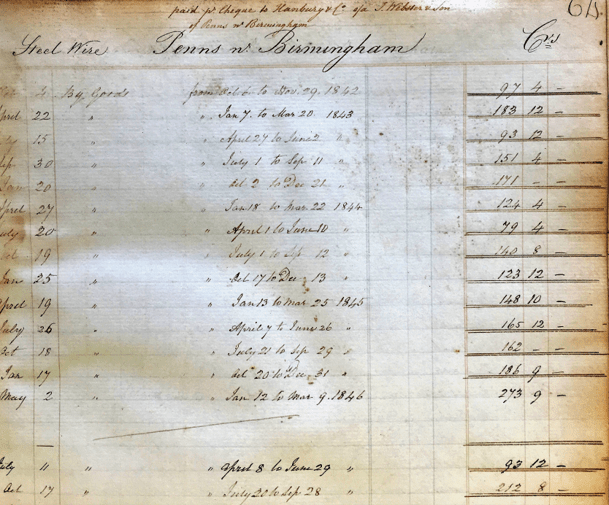

Throughout the 1840s, the most illustrious pianoforte makers of the day were using Webster’s music wire. John Broadwood and Sons, makers of pianofortes for the royal family and composers such as Chopin and Lizst, were dependent on Webster’s to supply it with the strongest wire obtainable at that time. The scale lengths of Broadwood’s design were initially determined by the strength of the available wire.

A page from Broadwood Pianos order book showing their purchase of steel wire from Websters of Penns. Order book 1843-1850 (d). Reproduced with the permission of Surrey Heritage Centre.

In 1840, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert bought a Broadwood Square for Buckingham Palace, where they played Mendelssohn together. As it was considered the strongest at that time, it is highly likely that Webster’s music wire was used in the making of this piano

Patent Steel Wire

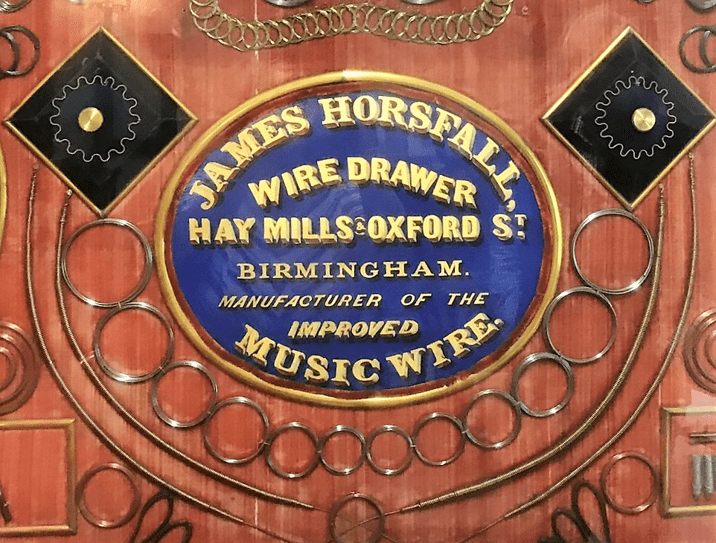

Despite the quality of their music wire there was always room for further improvement and this is the point at where James Horsfall became forever famously linked with steel wire production.

The ideal for music wire was to be strong and ductile but once manipulated, to retain its strength and ductility without breaking. As the Websters had experimented with manganese in producing steel, Horsfall experimented with drawing his wire with both heating and cooling agents until he discovered how to imbue his wire with all the requisite qualities.

Horsfall patented his process in 1848 and went on to win a medal at the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was soon realised that the combination of their innovations would create a market leading steel wire of superior strength and quality. Webster and Horsfall was formed in 1855 with James Horsfall’s patent being assigned to the company.

The Victorian era saw advances in all areas of life and industry and Webster and Horsfall have played their part in that story. Perhaps most famously, the company’s involvement in one of the most remarkable achievements of the age – the laying of the allowing communication between the old world and the new.

Not only was Patent Steel Wire vital to the musical instrument trade, it also made possible the coiled spring; which would go on to become an essential component of the internal combustion engine. Wire and springs are used in all manner of products, from pins and needles; bicycle spokes, cars and aeroplanes; ammunition and weapons; to the springs under the keys of computer keyboards. In its 300th year Webster and Horsfall continues to be a specialist steel wire manufacturer and stockist

Locked Coil Rope

In the early 1890s, yet another innovation and partnership changed the fortunes of Webster and Horsfall once more.

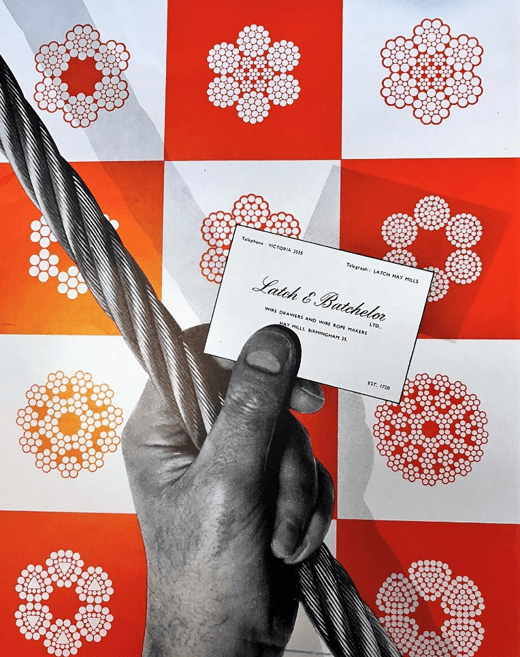

James Horsfall had died in 1887 but the company had passed to his adopted son, Henry Herbert Coldwell (later Horsfall). Henry had been apprenticed at the company and became an accomplished engineer, knowledgeable about the skills and practices of wiredrawing and the behaviour of metals. In 1892, Henry formed a partnership with Telford Clarence Batchelor and Arthur Latch.

Batchelor was an innovative draughtsman who enjoyed engineering problem solving, particularly the mechanical movement of machinery. He experimented with designs for an extraordinary new steel rope. His idea, to inter-lock the strands of wire as the rope was being manufactured. This required the strands of the wire to be shaped rather than round, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, to give the rope incredible tensile strength, a smooth surface and a smaller diameter.

Batchelor’s patented his design in 1884 and with his cousin Arthur Latch, had initially planned for the company, Glass Elliott, to produce it. Latch was an employee of Glass Elliott, a rope maker of distinction, noted for the manufacture of the Atlantic telegraph cable and their supply of wire ropes for colliery lifts.

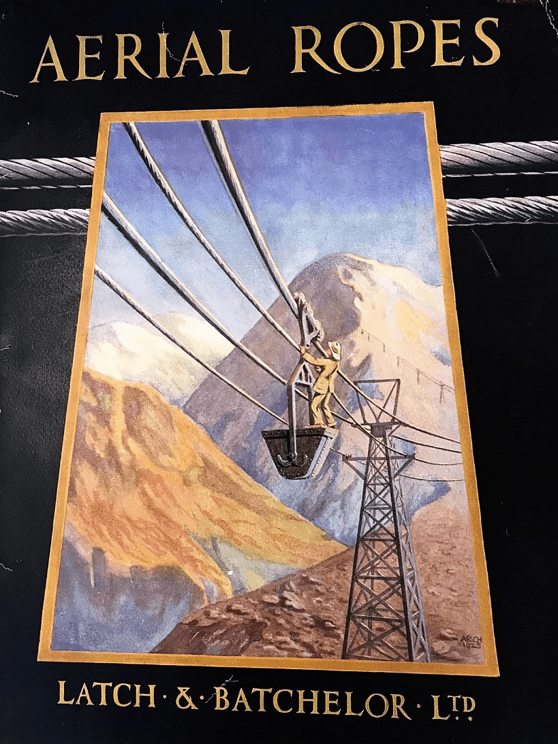

Note the different rope designs on this company advertising literature.

Note the different rope designs on this company advertising literature. Reproduced with the permission of Library of Birmingham, LS10/ Latch

Negotiations with Glass Elliott did not meet expectations and Latch turned to Webster and Horsfall, the sole manufacturer of Patent Steel Wire, the strongest wire known.

The journey was not smooth and after expensive trial and error, the combination of Patent Steel Wire and Batchelor’s design finally produced a market leading product; a steel rope five times stronger and more pliable than any other rope known at the time. Twentieth-century trade catalogues show how the company developed Batchelor’s 1884 patent Locked Coil and 1888 patent Flattened Strand wire ropes and also produced Lang’s and Ordinary Lay wire rope.

The Locked Coil innovation meant deep cast mining was possible and again Webster and Horsfall and Latch and Batchelor achieved a monopoly; this time in supplying colliery and mining winding gear.

During the first half of the twentieth century, new markets emerged and their wire ropes were used in sail ropes, rigging, suspension bridges and aerial ropes.

Latch and Batchelor supplied the 78mm diameter Locked Coil Wire rope for the Warragamba Dam, located approximately 65 kilometres west of Sydney in a narrow gorge on the Warragamba River. It is one of the largest domestic water supply dams in the world. The dam opened in 1960 and still uses the original rope supplied to this day.

After the decline in Britain’s core manufacturing industries and mining, the company refocused the business in the 1980s. Latch and Batchelor now concentrates on the manufacture of specialist mining ropes for export and the supply and service of high quality ropes and attachments.